(Reprints: Judge Dredd stories from 2000 AD Prog 208-267, 269-270)

This week, I've got the honor to be joined by the mighty Tucker Stone of The Factual Opinion fame!

WOLK: Ah, here we go--the volume where "Judge Dredd" really started to live up to its potential (halfway through, anyway). Also the volume where our action hero commits genocide.

Looking at this volume as a whole, the structure of '81-'82-era Dredd becomes a lot clearer: John Wagner and Alan Grant had a couple of big stories in mind, they wanted them to be drawn by a single artist, and they had to get them done way in advance so that there'd be time to get them drawn. "Judge Death Lives" is the longest complete Dredd story Brian Bolland ever drew, at 32 pages. But Bolland was very slow, and they had to buy him some time; hence the series of "Mega Rackets" two-parters. I can imagine Wagner and Grant trying to brainstorm cop-show clichés that they could riff on for twelve pages: "Numbers games!" "Hit men!" "The Mafia!" "Stookie glanders!" "'Stookie glanders'?" "I don't know, you tell me. I just made that up." (That's the only really inspired story in that sequence; I love the way Ian Gibson draws the meek little stookies.)

And then Carlos Ezquerra's return to Dredd for a 25-part story had to be given some serious lead time, so we got the "Block Mania" sequence that looks like it's going to hit its peak and subside, and instead keeps building until it tears open into "The Apocalypse War." (As it turns out, Ezquerra didn't quite make it all the way through--#268 had a reprint, and the last couple of episodes ran in black and white instead of beginning with a two-page color center-spread--but he also drew the two episodes following "The Apocalypse War," and 31 more over the following year. Note also that he stops drawing Dredd covers for this sequence after #256.) Ezquerra seems now like the classic early Dredd artist alongside Bolland and maybe McMahon, and he created the look of the character, but his only published Dredd stories before "The Apocalypse War" were way back in Progs #5 and 10.

Ezquerra totally nails this story, though--cranking up the tension and the scale of its frantically escalating acts of violence from episode to episode, pulling off crazy storytelling tricks without breaking stride. (The no-filled-in-black-areas trick he adopts for the flashbacks is blunt, simple and effective.) He doesn't do pretty, the way Bolland and Steve Dillon and a few of the other artists here do; his lines look like they're cut into the paper with a knife dripping mud.

Grant and Wagner start twisting their own knife as soon as this story starts, too. British boys' comics had a tradition of the brave warriors defending their land against the Hun or its Russian equivalent, but every venal thing the Sov-Blok does turns out to be something Dredd's perfectly capable of doing too. That's signaled from the very first episode, where the one-eyed Russian general sneers "The people? What have they got to do with it?"--and on the next page, Dredd snaps "The citizens? What makes you think they'd be interested?" Plus, it's a story about genocide with comedy relief interludes--the Walter-and-Maria slapstick routines, the Country Joe-type folksinger getting splattered by a missile.

More broadly, I love the way "The Apocalypse War" operates within the overall run of the series: the end of the war is presented as "well, that's over, we don't have to worry about that again, let's start rebuilding." Like you can just nuke Moscow and that ends that problem. "We begin bombing in five minutes," and so on. And then it keeps coming back to bite Dredd and Mega-City One in the ass, over and over--notably in "The Doomsday Scenario," and now again in "Day of Chaos." Contrast the end of it with the resolution of "Judge Death Lives," too: the spirits of millions of victims crying out for vengeance ("we didn't deserve to die!")... and, of course, Dredd has now effectively done exactly the same thing as the Dark Judges.

Anyway: almost 700 words and I haven't even gotten to "gaze into the fist of Dredd" yet. Take the mic, Tucker!

STONE: I've been fascinated by what I'd heard about the mega arcs of Dredd before, but I went into reading this the first time with no real idea how they were set up or played out, and so had no idea that the conclusion of Block Mania was going to initiate the beginnings of The Apocalypse War. I have to wonder--is this what the Batman editors were trying to achieve years ago when Cataclysm gave way to No Man's Land? It's always seemed to me that No Man's Land was an attempt to incorporate post-apocalyptic survival and a Mega City One style immediate brand of justice, but to see how Wagner and Grant (and if I'm understanding the history of this stuff correctly, the omnipresent editorial scythe of Pat Mills) expertly managed to deliver a conclusion that drastically changes tone and plot direction while still seeming totally organic to the story they've been telling (doesn't it seem like our Russian spy's plan places a lot of faith in the natural tendency of Meg City's citizenry to behave like selfish nihilists? Isn't that faith completely justified?)--it's utterly brilliant storytelling, and it makes the gigantic, absurd ex machina's that those Batman stories rested on seem like training wheels.

Let me back up for a second though, because while Apocalypse may be what sucked me in the most, I would like to single out a couple of things, the first being Colin Wilson's work on Diary of a Mad Citizen (outside of the core Dredd guys, Wilson is a great go-to for the perfect Dredd jaw, and the look on that robot secretary's face in the final panel is priceless) and the second is the Hotdog Run, which is one of my favorite iterations of the Dredd-schools-the-newbies story that seems to come up so often. I don't know how much of the recent Dredd stuff you've read, but the Cursed Earth portions that I've checked out in the recent UK collections published under the Tour of Duty banner have been absurdly entertaining, and a real testament to how Dredd's absolutism works when he's outside the immediate back-up forces he can call upon in Mega City One. When he decides to hold the line in a Cursed Earth stand-off, it has a Butch Cassidy/Wild Bunch quality that's quite appealing, and I might even extrapolate it further--it's all under the same umbrella of faith-in-strength, faith-in-my-righteousness that sees Dredd through in the Judge Caligula story or the Apocalypse War. (And that comes up later, in that story where everybody gets infected by fatal mushrooms.) It's what Wagner seems to be playing with in the current Tour of Duty stuff--Dredd doesn't care that he has cancer, but he is bothered that his holy justice does such a disservice to his distant, mutated cousins. It's a level of emotional complexity that I think Wagner has grafted onto the character in recent years, but there is a retroactive precedent to be argued for in these early stories: here's Dredd at the heart of his successes, the apex of his brand of justice. He does always survive these fights, he does make the right, horrible calls when he has to, and that's because he hasn't become an old man yet. When you compare the moment where he puts millions to death here (or when he exterminates traitors in a shallow grave) to the moment where he puts billions to death in Judgment Day, there's a genuine sense that you're watching a different person's behavior--he did what he had to do in Apocalypse War, and he was proud to do it not because it involved killing people or being right or even winning, but because doing what one has to do (whatever the circumstances dictate that being) is what Judge Dredd is born, trained and ready to do. Nowadays, there is a sense of burden to his choices--the burden of being alive, of knowing that no one else could bear up underneath it all.

I've gotten a bit off track here, haven't I? Talk to me Douglas: am I still in the stadium? Should I consider different avenues of employment? Would your Dredd and my Dredd get along?

WOLK: Your Dredd and mine would totally make out.

I've read a bunch (not all) of Tour of Duty, and I really like it. But I suspect there's always a backhandedness to any time Wagner and Grant show us Dredd as a hero who triumphs because of his absolutism--the big picture of Tour of Duty is that it's about Dredd getting assigned to oversee a forced relocation camp for genetic inferiors. Even his softening on civil rights, excuse me, mutant rights issues isn't because of any realization of what's right: he changes his perspective only when it affects him personally, when he discovers he's got mutant relatives. (And it's kind of great that he is an old man now. His body's starting to fall apart on him, he's making some questionable calls and grumbling about his co-workers' ideas, his seniority has gotten him appointed to a position of authority that doesn't suit him at all, etc.)

Great call on "Cataclysm" --> "No Man's Land" echoing the structure of "Block Mania" --> "The Apocalypse War": I think this was the period when Dredd really clicked into being one big serial that could keep moving forward, however incrementally and episodically, instead of being a franchise that always had to revert to its classic formula eventually. The death of Judge Giant Sr. in "Block Mania" underscores that: it's not presented as a big dramatic turning point, it's just bang, his number's up, and that's what happens when you're a Judge.

You're right on about Orlok, too. Whatever it is he's got in that magic block-mania serum, it seems to work--the scene where finally Dredd loses his shit and announces that he's fighting for Rowdy Yates Block nicely inverts the usual "he's no ordinary man and nothing can break his resolve" formula. (Rowdy Yates--I had to look it up--was the character Clint Eastwood played on Rawhide.) Although "Judge Death Lives" gives us the classic "he's no ordinary man" moment: the "gaze into the fist of Dredd!" sequence. What a brilliant scene: metaphysics vs. brute force, and brute force wins.

I think there's a distinction between Dredd's mass slaughter in Judgement Day and here, though, and it's different from the one you're suggesting. I haven't read Judgement Day in a while, but as I remember the "unleash the nukes" moment is framed as desperate defense of humanity, and it's suggested that those cities were probably lost already anyway. What Dredd does in The Apocalypse War is straight-up political violence--no sense of proportionality or discrimination, just kill-'em-all. (Consider how the story ends if he doesn't nuke East Meg One, or doesn't nuke all of it: pretty much the same way. All he really has to do is destroy their supply base and get rid of the commanders, and MC1 wins.) I think that's why this is the moment that keeps resonating for the rest of the series, the one that turns Dredd into, arguably, a war criminal. (EDITED TO ADD: Duncan Falconer, over on Twitter, points out Garth Ennis's essay on Dredd's genocide.)

I'm pretty sure Pat Mills wasn't involved with the editorial side of 2000 AD at this point; Tharg, during the 1978-1987 period, was Steve MacManus, who deserves some kind of prize for talent-spotting. The second half of "The Apocalypse War" was the period where I first started picking up 2000 AD in earnest (having seen a couple of issues from a few years earlier)--I was in London, went to Forbidden Planet, and bought every issue they still had on the new racks. There was no other British "boy's comic" that was anywhere near this level in those days--Barry Mitchell's art on "The Synthetti Men" looks much more like everything else that was around at the time. (That's a Bolland cover, not Mitchell, a few lines below this, by the way.) That era of 2000 AD, though, had Alan Moore writing a ton of Future Shocks (huh, I thought, I'd better keep a lookout for this guy's stuff), Mills and Jesus Redondo doing Nemesis, Bryan Talbot developing very quickly, Ian Gibson and Massimo Belardinelli at the top of their game... and also The Mean Arena, but you can't win 'em all.

Gas face to whoever assembled this version of the material in this volume, though--there's some really bad reproduction, especially on the last chapter of "Block Mania," where some of the lettering is barely readable (and a lot of Brian Bolland's final Dredd story to date gets smeared, too).

So let me ask you this: a lot of what you've singled out about this period of Dredd has to do with its dramatic force and escalation. How do you feel about the slapstick and broad satire that keep turning up, even in the super-gritty parts of the story? To paraphrase Adorno, can there be comedy after East Meg One?

STONE: I helped set up a 2000AD focus group a few months ago, one that existed so that they (2000AD) could get a chance to speak with a bunch of American comics readers who weren't aware of 2000AD's output. It was an enlightening experience--validating some personal theories, shining a light on own presumptions, like that upcoming movie The Help, but more about Future Shocks--but the one specific instance that sticks out was a minor one, and that was one of the participants claimed to be uninterested in Dredd, saying "honestly, I just don't want to read about some supercop." And to a certain extent, I can understand what that guy was talking about--as long as you're not using that description to talk about Judge Dredd comics. For me, the undercurrent dynamic of Dredd that makes it so evergreen, the thing that keeps me invested even when those lessor artists or non-Wagnerian scribes come aboard is that sense of humor that you've brought up. It's the neverending pokes at America, or the way Dredd's world constantly animates that final, extreme conclusion of so many of this countries fantasies and ideals. You want to worship General Patton? East Meg One is where that worship reaches its fruition. You want to dress your kids in branded clothing and fast food advertisements while they slurp up 96 ounces of sugary shit? Hey man, the proles in Margaret Thatcher Block gotta come from somewhere.

And here's the thing, Douglas, here's why I keep coming back to this stuff: none of these gags and jokes and satire are totally fresh to Dredd, and a lot of them--specifically the ones where they're going after game shows, entertainment and pop culture--are that hard to come up with. What is hard to do, and what these stories keep pulling off, is being able to do it with seeming like an irritating teenager who just read Naomi Klein's No Logo. It's making stories that make fun of America without sounding like Adbusters, and that's hard as hell to do. Accomplishing all of that while blatantly embracing the absolute thrill (and it is Absolutely Thrilling!) of witnessing Dredd as he punches his fist through the heads of the same death worshipping fascists who stole my Danny away from me--that, for my money, is why these comics are such an incredibly huge success and have been one for so long. There's a near impossible alchemical mix of humor and pulse pounding action that's apparent in Dredd's best stories, and the Apocalypse War is a definitive blueprint of a "best Dredd story."

WOLK: It's true: one of the things I think is sort of amazing about Dredd is that it's a satire of American culture, by and for British people, and it's never short of material. I think one way to read "The Apocalypse War" is as a very darkly satirical riff on American militarism and paranoia--as the kind of heroic narrative of unprovoked attack from outside and righteous retaliation that Americans imagine. (But that's also the sort of narrative 2000 AD had been feeding its readers with a straight face a couple of years earlier, with "Invasion.")

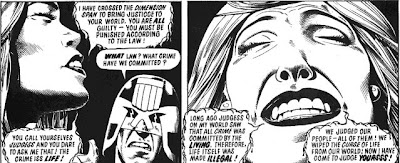

Maybe the weirdest angle on that is the version of "The Apocalypse War" that Ron Smith drew. At the time, Judge Dredd was appearing in a weekly gag strip by Wagner, Grant and Smith in the Daily Star; three months after the war sequence ended in 2000 AD, they published a ten-panel version of it as a newspaper strip. Here's how it ends:

That's Reagan (etc.)-era America right there: "next time, we get our retaliation in first." An apocalypse with a punch line. Which brings us to next week, when I'll tackle the Daily Star Mega Collection, which assembles most of the first few hundred newspaper strips.